by Dauna Coulter and Dr. Tony Phillips

Safari, anyone? Citizen scientists are invited to join a hunt through the galaxy. As a volunteer for Zooniverse’s Milky Way Project, you’ll track down exotic creatures like mysterious gas bubbles, twisted green knots of dust and gas, and the notorious “red fuzzies.”

“The project began about four months ago,” says astrophysicist Robert Simpson of Oxford University. “Already, more than 18,000 people are scouting the Milky Way for these quarry.”

The volunteers have been scrutinizing infrared images of the Milky Way’s inner regions gathered by NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope. Spitzer’s high resolution in infrared helps it pierce the cloaking haze of interstellar gas and dust, revealing strange and beautiful structures invisible to conventional telescopes. The Milky Way Project is helping astronomers catalogue these intriguing features, map our galaxy, and plan future research.

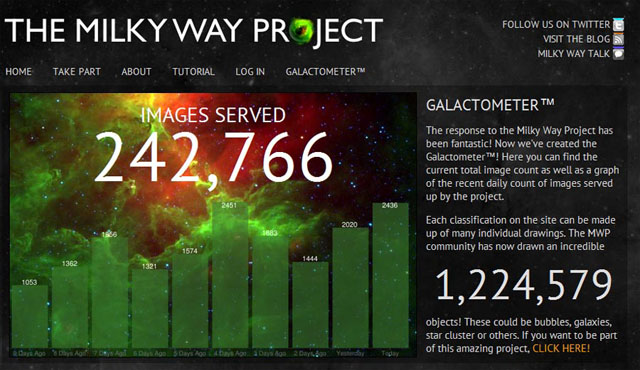

“Participants use drawing tools to flag the objects,” explains Simpson. “So far they’ve made over a million drawings and classified over 300,000 images.”

Scientists are especially interested in bubble-like objects believed to represent areas of active star formation. “Every bubble signifies hundreds to thousands of young, hot stars. Our volunteers have circled almost 300,000 bubble candidates, and counting,” he says.

Humans are better at this than computers. Computer searches turn up only the objects precisely defined in a program, missing the ones that don’t fit a specified mold. A computer would, for example, overlook partial bubbles and those that are skewed into unusual shapes.

“People are more flexible. They tend to pick out patterns computers don’t pick up and find things that just look interesting. They’re less precise, but very complementary to computer searches, making it less likely we’ll miss structures that deserve a closer look. And just the sheer numbers of eyes on the prize mean more comprehensive coverage.”

Along the way the project scientists distill the volunteers’ data to eliminate repetitive finds (such as different people spotting the same bubbles) and other distortions.

The project’s main site (http://www.milkywayproject.org ) includes links to a blog and a site called Milky Way Talk. Here “hunters” can post comments, chat about images they’ve found, tag the ones they consider especially intriguing, vote for their favorite images (see the winners at http://talk.milkywayproject.org/collections/CMWS00002u ), and more.

Zooniverse invites public participation in science missions both to garner interest in science and to help scientists achieve their goals. More than 400,000 volunteers are involved in their projects at the moment. If you want to help with the Milky Way Project, visit the site, take the tutorial, and … happy hunting!

You can get a preview some of the bubbles at Spitzer’s own web site, http://www.spitzer.caltech.edu/. Kids will enjoy looking for bubbles in space pictures while playing the Spitzer concentration game at http://spaceplace.nasa.gov/spitzer-concentration/.

This article was provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Caption:

Volunteers study infrared images of our galaxy from the Spitzer Space Telescope, identifying interesting features using the special tools of the Milky Way Project, part of the Citizen Science Alliance Zooniverse web site.